Private Pilot Achieved!

Scroll DownThe journey is just beginning - but let’s recognize a milestone when it happens; on June 24th at 11:30AM Pacific time, I passed my official FAA checkride and was issued my Private Pilot certificate with Airplane Single-Engine Land (ASEL) rating.

This, after thousands of miles flown in twelve different aircraft across nearly sixty individual flights, eight instructors, hundreds of landings at a dozen different airports day and night, countless unbookable hours in my home simulator, endless tests and a lot of swearing at western Washington’s finicky weather in all four seasons.

Any good trip is worth a debrief - so let’s talk about it. Specifically through the lens of a prospective student who wants to go the same route - what should they know that I wish I knew when I started?

What Did It Take to Achieve?

Probably the big question from any prospective pilot is “what am I getting myself into?”

You’re going to care about:

- What it costs

- How much time it takes

- How difficult it is

- What value comes out of having it

- And what it takes to keep it after you get it

And – you’ll find a million articles about this everywhere else on the web, so here’s what I can uniquely offer you.

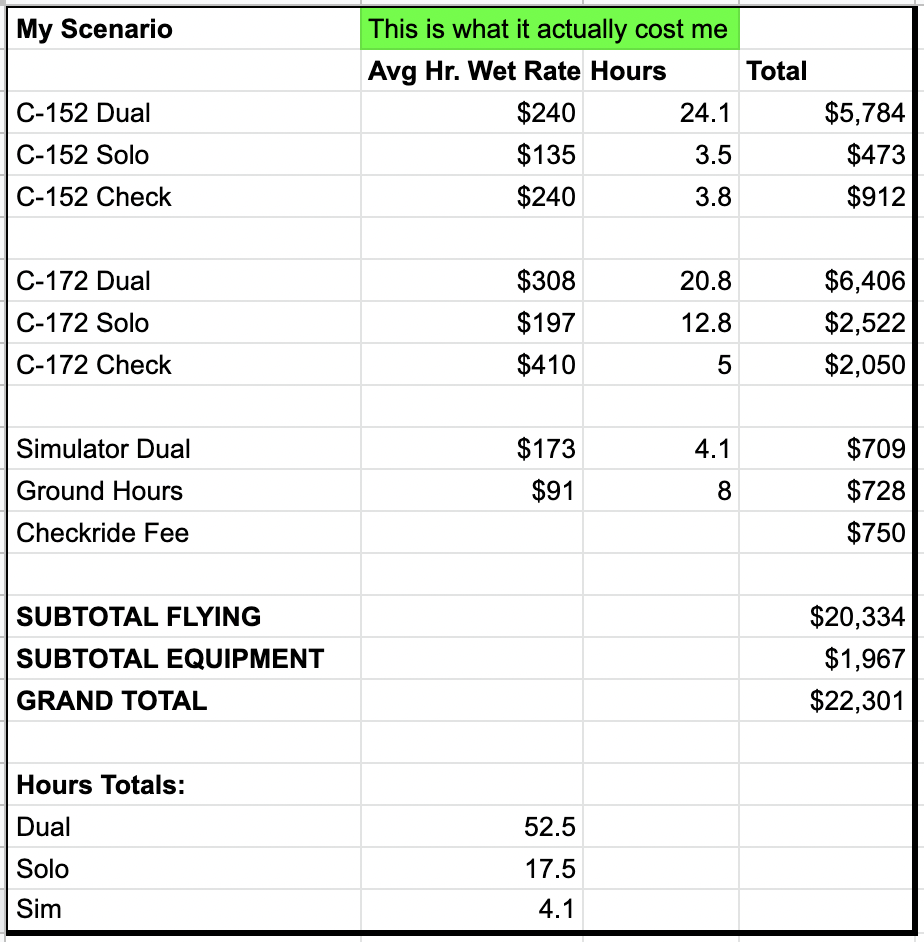

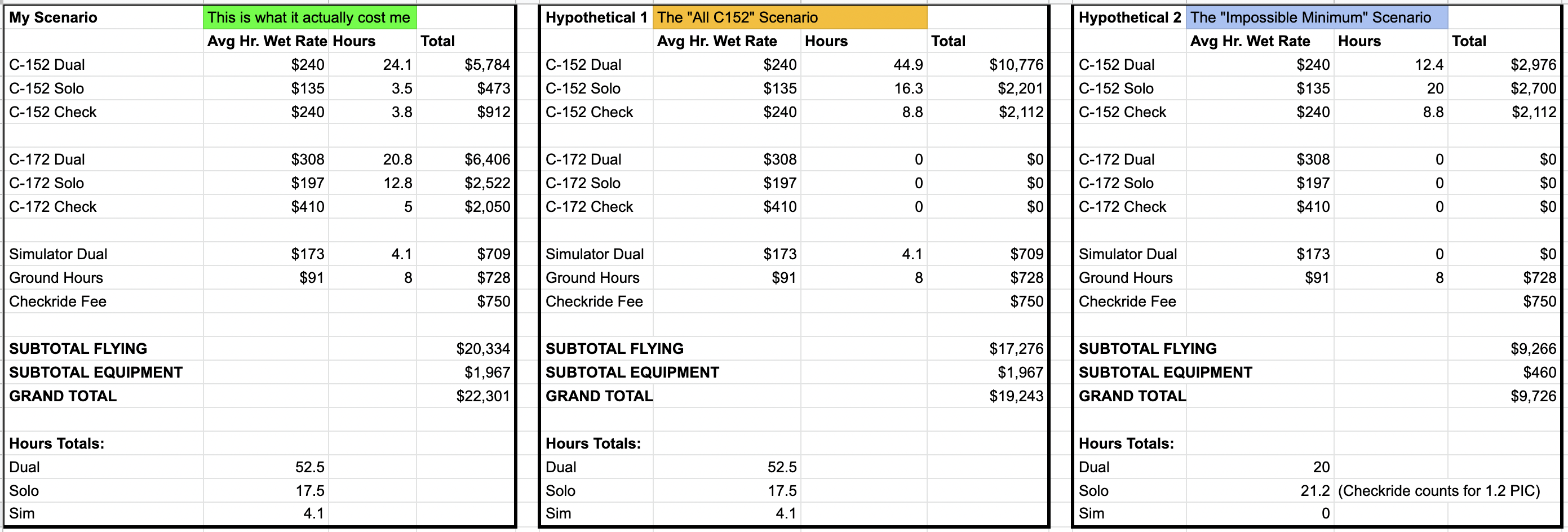

A spreadsheet. Here’s the link for you to explore it yourself, analysis and screenshots below.

What it cost me in money and time

To get my PPL it took 50 flights and 70 hours booked over 11 months, and cost about $22,500.

Findings:

- I flew 2x weekly in summer and fall, reduced to 1x weekly in winter and spring.

- My ratio of Dual flights to Solo flights was about 3:1.

- Dual flights cost about 50% more than solo flights.

- Half my flights were in a plane that was 50% more expensive.

Split into three “stages” along the path, it took me the following time and money to achieve each:

- To first solo: 4 months, 24 flights, 26 hours, $8,000.

- To first solo cross country: 5 months, 13 flights, 35 hours, $8,000.

- To checkride completion: 3 months, 8 flights, 21 hours, $6,000

Can you do it cheaper and faster? Probably.

Let’s add on two hypothetical scenarios and compare to my actuals:

- A “small plane” scenario to see how much I’d save if I stayed in a C-152 all the way through.

- A “bare bones” scenario to see how much money the absolute minimum of flying and equipment can save.

Here are my findings on these scenarios:

- Plane type doesn’t matter as much as hours. Gas is gas, and it’s the primary driver.

- Solo time vs dual time can make a dent, but there’s a practical minimum.

- I probably could have saved 20% reasonably, but a 50% savings is pushing it.

Be aware: some of what you spend, especially on hours, won’t be entirely up to you. Your CFIs at your school are the ultimate arbiters of whether you’re allowed to progress, ready for your checkride and so on, so the number of hours you build have a practical minimum: what it takes to convince them you’re ready.

What I was told about hours when I started my journey mostly came true in the end:

“The rules say you need 40 hours. You'll end up closer to 80.”

Where you land, between the mythical 40, and the more realistic 80, is going to drive your PPL cost more than anything else.

The good news is you can spread it over an number of months, taking lessons and building hours only when you want to spend the money. The stages came out to be pretty evenly priced for me, and likely will be for you, too.

I suspect there’s a very special someone out there that wants to get their PPL for under $10,000 these days and can probably do it. But to be a contrarian, I think there’s a lot of sacrifice that’ll be tied up in that number and it may not be the best thing to optimize for. Quality of training, number of hours to build experience, dual vs solo time, building up equipment you’ll continue to use - these are all things that might get put aside to chase a cheap PPL, and I’m personally glad I didn’t go that way.

What’s Hard vs Easy?

This is a category of question I was dying to know when I started. “Where did you get stuck?” is something I asked a lot of my pilot friends. I should have also asked “what was a breeze?”

Get a Part 61.

I’ll start with what could have been hard but made easier: It’s been a grind to get my PPL training done while in the middle of a full-time job. If you’ve got a job, be sure you go to a part 61 school. The curriculum is more fluid and you can take lessons out-of-order. A 141 school may seem attractive due to fewer overall required hours but it’s not worth it if your time isn’t completely your own.

The Hard Stuff

Next - here are particular difficulties you are going to want to build in some time and planning for:

- The written test. Get a ground school that offers practice tests and take them until you get over 80%.

- Oral exams. Study for and pass your written test early, so that you’re thinking the kinds of questions your examiner will ask you (as many are the same). Buy the oral exam guide and have a friend quiz you.

- VFR airspace weather minimums. Several tables and charts all failed me here. Nothing worked until I heard of the “VFR Weather Triangle”. Look it up. Rod Machado seems to have come up with it.

- Nav and weather planning your cross-countries. These are a lot of fun to do (if you’re a nerd like me) but also take more time than you think. Book out at least two hours to build your nav plan and two hours to correct it for weather and brief, every time. Don’t get rushed.

- Rudder coordination. Now why would I ever have a problem with this? I don’t know - but I’m still stuck on it. I think I learned some bad sim habits and fail to do a smooth connection between starting a bank and plugging in rudder smoothly.

- Task division between GPS/Foreflight and eyes-up flying. Having a supercomputer on your knee is amazing, especially when combined with a Sentry ADS-B unit. But you only get about 6 seconds at a time to look at it, and when you’re in a rush, you fat finger everything and it all goes wrong. Flicking eyes between eyes-up flying, and back down to the GPS still messes with me, and I feel task-saturated, which contributes to mistakes.

- Soft-Field landings. Nobody teaches these right in land-based airplane schools, and as a result, you’re going to have a hard time convincing a check instructor or examiner you know how to do them. My advice - ask several instructors along the way and get them to demonstrate and check your understanding of it.

- Understanding everything about weather. This is a trick. You won’t be able to understand everything about weather (seriously, can you name the 10 kinds of fog?), and the truth is you won’t have to. It’s hard to know exactly what your check instructors and examiners will ask about weather but it will probably be about these things: fronts, thunderstorms, ice, wind shear. What do they have in common? They kill pilots.

And finally -

- Task saturation. This is the hurdle that cracked me as an early student. On a particularly bumpy, cloudy day in the compression wave of an oncoming cold front, I hit traffic, turbulence, a failed stall, followed by shock cooling as we came down in altitude. There was too much, too fast, and I felt like an absolute failure of a pilot.

If this happens to you, remember:

“Aviate, then Navigate, then Communicate. You'll be okay!”

The Easy Stuff

Was there anything easier than I expected? Yes indeed, this can happen, and it did for me in a few places:

- Reading charts. It may be because I came from the world of sailing and nautical charts have some serious overlap with aero -nautical charts. About the only thing that got me stuck is the magenta and blue silhouettes that demarcate Class E space.

- Landings. This isn’t about getting them perfect. You never will - and you should never stop trying - but you can absolutely overthink landings and mess yourself up. For me, it became an integration exercise between hitting the right speeds on the flow, and maintaining a proper sight picture, and it felt very natural, very early.

- Ground reference maneuvers. Hit your entry speed, stay on speed, control your altitude. Watch a ground point; no matter what the wind is doing, fly the ground point.

- Radio comms. I’ve always wanted to be a game show host, so being on a microphone doesn’t give me a lot of agita. I hear there’s a lot of sweat and tears in early pilots around getting on the radio. I might have practiced in the shower.

You’ll have your own moments where things just “click”, and that will give you energy to get past the hard moments that will come.

How Was the Checkride?

There’s a lot of pent-up worry about how the eventual day with the DPE will be. Will the checkride be fun? Scary? A tale of tragedy?

Okay, maybe that was just me. But the fear was real. In my own mind I pumped up the fear of a crabby chief pilot from hell, putting me on my back foot every moment, making me feel completely unprepared to be a pilot. Maybe this worked in my favor - I put a lot of pressure on myself to ace my pre-checkride stage checks, and not wait to test myself until the end.

But still - the day came. And here’s what you should know about it:

- They aren’t here to crush you. They’re looking that your school has done their job in teaching you good habits. One or two misses aren’t going to sink you, but if you’re exhibiting a pattern of continued bad behavior, they’re going to disqualify you.

- You get credit for success. Let’s say you get disqualified. You get credit for everything you did right, and may also be able to finish out the rest of your checkride for more successes - and only have to come back to redo the very specific things you got wrong. You will need to have your CFI fly with you for another dual and sign off that you’re OK to re-examine.

- They aren’t allowed to teach. This is a little silly - but this is more for your examiner’s benefit. The FAA says the examiner is here to examine you, they are not an instructor. So if you learn anything during the checkride … and you might … don’t make life hard for your examiner and say to anyone that they “taught” you something. Don’t expose them to any FAA criticism; they didn’t teach you. You just happened to “realize” something, OK?

By the time you get to your checkride, you are (or should be) a confident early-stage private pilot. You’ve been through the tests. You have the hours. You have the backing of your school. As the pilot in command it’s your job to take your examiner up and give them a pleasant, professional ride, and you should know whether you can do that.

I walked out onto that ramp feeling confident and ready to go, remembering the best quote I heard about the checkride:

“Your examiner is just your first passenger as a private pilot.”

Last Thoughts

So - a nearly year-long journey is at an end, and a new one is beginning: learning more on my own than with an instructor in the seat. Remember, you don’t have magic skills that appear when you finally pass that checkride. You come out of that checkride with the same experience you went in (your examiner can’t teach you anything, remember?). So don’t get cocky - remember most of your job as an early private pilot is to learn more, safely.

And - have a good time doing it. It’s flying, after all.

The Final Lesson - Be Prepared

I’m not new to flying. I feel like I’ve prepared my whole life for the journey to being a pilot. From early days learning flying from my father, to the early simulators, to Space Camp, flying has been around me and waiting for me to come back.

But coming into flight training at 40 years old, I brought an experienced, systematic approach to learning that I’ve built up over decades, that I think served me well. It’s just three simple rules:

- Learn from those before. Ask, talk, read. Write your understanding of what it takes and get it reviewed. Know the plan, know it’s right.

- Build a minimum commitment and execute. If it takes 100 hours or 1000, break it into weeks and commit the time, do not falter.

- Always have your list of “work-ons”. Know your hard areas and commit to do better on them every time.

I know I did it right. I did the interviews. I built the plan. I tracked my progress and work-ons.

And – I doubled my commitment by making flying - and simming - a whole thing, right here on this website, making myself accountable to those minimum commitments, among my family, friends, and suscribers.

Life intervened. It wasn’t perfect. But I did it - I’m a pilot.

You can do it, too.