Flying the Virtual Skies - a Museum of Flight Show

Scroll DownFlying the Virtual Skies is an episodic video series presented by The Museum of Flight, developed by Charles Cox and the Future Leaders Team. It combines modern flight simulation with real expert interviews, to give viewers a unique “being there” experience on historic aircraft. Using lessons learned in the GiveBig 2020 Livestream, this series continues the Future Leaders’ commitment to exploring new audiences and supporting Museum development.

Episode List

The following episodes of Flying the Virtual Skies are available to watch:

Episode 1: Concorde

- 45 minutes episode time + 30 minutes Live Q&A

- Starring Mike Bannister, Concorde Chief Pilot British Airways, and Ian Smith, Concorde Chief Engineer British Airways.

- Route is EGLL-KJFK.

Episode 2: The Boeing 707 Barrel Roll

- 45 minutes episode time + 30 minutes Live Q&A

- Starring Mike Lombardi, Boeing Chief Historian

- Pilot: Alec Lindsey, FO: Zach Sweetser

- Route is KBFI Airshow Loop

Episode 3: P-51 Mustang

- 90 minutes episode time + 15 minutes Live Q&A

- Starring Jason Muszala, Director at Flying Heritage Museum \ Mike Lombardi, Boeing Chief Historian

- Pilot: Alec Lindsey, Wingman: Charles Cox

- Location is Normandy, France (WWII)

Our Support and Sponsors

We are grateful to The Museum of Flight for giving us the opportunity to innovate as the Future Leaders Team, and for their trust and partnership with us as we developed this unique programming to help drive the Museum’s aviation excitement into the digital world during the Covid-19 crisis.

How and Why Was This Produced?

The Future Leaders Team exists to support The Museum of Flight with development, outreach and new audience efforts, focusing on young professionals. In early 2020, the Covid-19 crisis had forced the Museum to shut its doors to the public and refocus its efforts virtually. The Future Leaders Team built this new type of programming as a pilot to reach enthusiast audiences without the need for a physical Museum presence.

Principles and Plan

The development of Flying the Virtual Skies builds off lessons learned in the GiveBig 2020 Livestream presented earlier in 2020. The key question: Can a compelling, Museum-worthy flight simulator experience be delivered in a 45-minute show?

Here are the principles we tried to stick to:

- Flying, First: Principal topic is flying an aircraft.

- Interviews, Second: Must have at least 1, preferably 2 special guests as interviewees.

- Museum or STEM Relevant: Must be relevant to Museum’s mission, collection, locations, or people - or is sufficiently relevant to STEM education to be of general interest to the Museum’s audience.

- Has a Story: Must have a “narrative” of human or historical interest: “Introducing the airplane” is not a sufficient narrative. An interesting guest over interesting terrain might be sufficient.

- Simulator-Ready: Aircraft flown must be available for one of the following flight simulators: “X-Plane 11” or “Microsoft Flight Simulator (2020)”. If special interactions are needed beyond takeoff, flying, navigation and landing (such as paradrops or slingloading), this must be available in the simulator along with the aircraft.

- Done in 45 Mins: Can be a reasonably “complete” flight experience in 45 minutes - time skips are allowed.

- Looks Interesting: Must be visually interesting through a combination of flown over location, aircraft interior/exterior, flight mechanics and maneuvers. In general, night flights do not qualify.

- Fly Right: Must focus on good sense operation and respect of the aircraft - not reckless or negligent operation as a rule. Extraordinary maneuvers are allowed if these were historically done (test pilots, failure recoveries) or critically relevant to the narrative.

- Leave Space for Interviews: Within 45 minute span, at least 20 minutes must be “peaceful” enough to conduct interview(s).

- Can Be Done Semi-Live: Must be flyable with a live audience watching on the Internet. Time skips are allowed, see “Has Segments” below for how to cover gaps.

- Has Segments: Must have at least two “pre-canned” segments that are used to set the scene, deliver historical context, explain a scientific concept, or otherwise bring narrative or Museum relevance to the flight. These segments can be spliced into the live feed to cover time skips in the flight.

Shopping the First Episode: Concorde

Idea generation started in June 2020, about a month after GiveBIG. An early frontrunner was the Aérospatiale/BAC Concorde - a favorite at The Museum of Flight, whose own Concorde G-BOAG, was delivered by Captain Mike Bannister in 2003, at the retirement of the Concorde program.

The hook, at the time, looked like this:

The Phil Collins Concorde flight - can you really beat the time zones (and race the sunset) back across the Atlantic from UK to US to get Phil to the concert stage in time to do his show in two places?

Here’s the story on Phil’s flight. We believe he took BA 003, which departed 19:30 London time, landing 18:25 NY time. Source here.

From idea to landing a timeslot took about two and a half months. By September, based on the success of GiveBIG 2020, we were able to schedule a timeslot with The Museum of Flight for the show on November 21st, 2020.

We had about ten weeks to deliver.

The Simulator and Airplane

As with previous shows such as GiveBig 2020, Charles’ Project Nimitz flight simulator hardware would be used, powering a copy of X-Plane 11 Pro, with the X-Vision plugin, XCamera, and a host of other smaller add-ons. At the center of the flight would be the Concorde itself, simulated by the Colimata Concorde FXP.

The route was originally based on the historical route of BA 003, the “Phil Collins” flight from London Heathrow to JFK Airport in New York City.

Charles began solo training on this Concorde route, creating several videos to gather experience and clock timings on each flight phase:

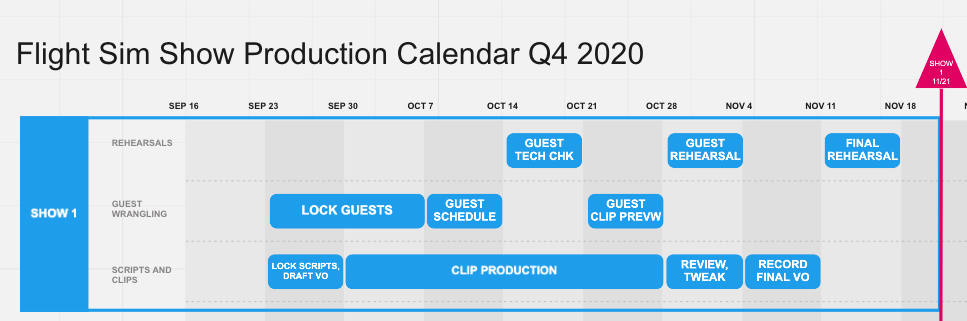

Building the Two Timelines - Show and Production

Next was building out the two timelines - the timeline of the 45-minute show, based around the Flight Profile of the Concorde aircraft, and the calendar timeline of the physical show building and asset delivery, which needed to land the entire episode by November 21st for the final show date.

Show Timeline

Click here for a larger timeline

Click here for a larger timeline

The phases were timed out from Charles’ practice runs, and any areas where compression was needed to hit the 45-minute mark were flagged.

The original plan was to use the pre-recorded segments to “hide” compression areas, allowing Charles to reset the simulator correctly while a pre-recorded video played to the livestream audience, when the video was complete, action would return to the simulator, now further along its route and ready for the next phase of flight.

Production Timeline

The production timeline needed to keep in mind the following parallel tracks -

The production timeline needed to keep in mind the following parallel tracks -

- Guest familiarization and commentary development

- Pre-recorded clip creation, refinement, and voiceover recording

- Practice time in the aircraft along the expected route

- Full rehearsals with guests, aircraft, and clips to land timing

- Time for Museum and guest review of all materials

The Guests Lead the Way - How the Show Changed

Guests are the most important part of Flying the Virtual Skies. With such an emblematic aircraft as Concorde, it was crucial to find guests that could speak to the aircraft’s legacy, technical specifications, feel of flying, and other topics of interest.

Thanks to the Museum, we ended up finding first Mike Bannister, Chief Concorde Pilot, British Airways, and then through him, Ian Smith, Chief Concorde Engineer, British Airways.

In early discussions on the show, the format, the audience and particular challenges of this type of show, we kept the following mantra in mind: Celebrate and Honor Concorde. It is a legendary aircraft, touched by both triumph and tragedy. We would treat it - and her crew - with great respect.

As information began to flow both ways, we shared artifacts like our schedule and our early practice videos. Our guests shared their own artifacts: charts, logs, checklists, and feedback about our practice sessions - many of which needed serious help.

To make things even more interesting, Mike and Ian were in the United Kingdom, GMT+0 timezone. We were in Seattle, GMT-8 timezone.

It became quickly apparent that several significant show changes were needed to be successful:

Fully live was not an option.

This was the most uprooting change, and forced an entirely new production pipeline to be developed. However, the reasons for this were sound: through review of our practice runs, our guests let us know how complex each phase of flight truly was, and how much the simulator would have to be reset at each phase to take into account everything that the crew did along the flight route. It was also discovered that many of the avionics system settings did not correctly save when saving a flight configuration (known as a “Situation” in X-Plane). These two factors combined meant that a fully live show risked far too many errors when reconfiguring between phases.

A co-pilot was required.

Not only was a solo pilot not historically accurate to Concorde, it was also not wise for a show about Concorde. Starting with the first guest reviews of Charles’ practice runs, Alec Lindsey, a fellow Future Leader, as well as an airline pilot and certified flight instructor, pitched in to help the show by putting together sim-ready checklists, vetting details with our guests, and accompanying Charles on his practice flights, running checklists and providing valuable feedback and cross-checking throughout procedures. The show rapidly became better, tighter, more precise, and it was clear that having Alec as co-pilot made for a better experience all around.

Drop the Phil Collins angle.

As said before, guests are at the heart of Flying the Virtual Skies. Mike and Ian brought so much of their own expertise, their own knowledge and personality to the show, an additional narrative conceit was no longer necessary - plus it added additional risk and fraying of focus. While it was regrettable to not be able to tell this particularly interesting historical story, the refocus on our guests was the right choice.

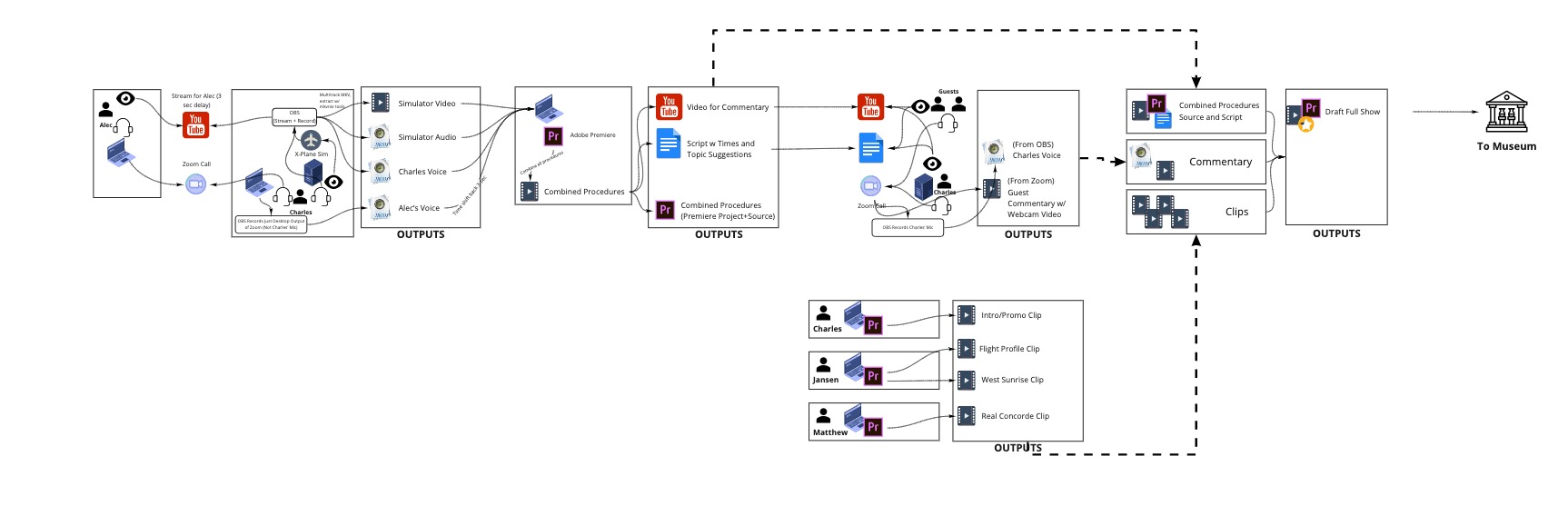

The “Like-Live” Production Pipeline

The reality was clear: we couldn’t manage the Concorde procedures, our guest interviews, and cueing up segments all in a live format without something going wrong. And with our guests and the reputation of this aircraft at stake, that wasn’t an option.

If we had separated live production pipelines where more than one person could handle each task - a pilot to fly, a host to interview, a producer to cue and manage the streams - it might have been a different outcome. However, in a pandemic where people aren’t able to congregate, each one of those roles then requires a signaling and coordination mechanism of some kind over the Internet, which imposes additional delay, complexity, and risk to all other parts of the show.

We had to decide where to spend our effort. What and how much did we want to re-invent?

Time remaining: Two and a half weeks until showtime.

We were fortunate to also get two other great people helping us, Jansen and Chelsea, who were going to develop one of our pre-recorded segments. The Museum’s own senior curator, Matthew Burchette, agreed to film a segment inside the actual Concorde at the Museum. We agreed to drop the third segment for simplicity’s sake.

The Goal: Like-Live

We needed to reconfigure the original GiveBIG 2020 production pathway with the following mantra in mind: How could we create a pre-recorded show between guests in the US and the UK, that FELT live?

Here’s how it worked:

The New Production Pathway

Click here for a PDF version of this beautiful thing

Click here for a PDF version of this beautiful thing

Here are the basic steps to follow along:

- Record Alec and I doing procedures inside the simulator, and a selection of “beauty” outside footage

- Playback procedures (along with written cues at various timecodes) to our guests and record their commentary video

- Overlay guest commentary video back over the procedures

- In parallel, receive pre-recorded clips from Matthew, Jansen and Chelsea

- Combine all commentaried procedures, beauty footage, pre-recorded clips, and front/back matter into a final 45-minute show

- Make drafts available for review with enough time to make fixes prior to final

- Provide final 45-minute show to the Museum for live-streaming before show date.

Here are the key technical findings and recommendations for anyone interested in doing a similar show:

Multi-track audio at ALL COSTS

I made a bet that much of the post-production difficulty would be lining up audio among these components:

- The simulator audio/video

- My own voice

- My copilot’s voice

- Our guests voice/video

If this was all one stream, it would be impossible to “Frankenstein” audio around as needed to overcome issues of timing, of overlapping, awkward silences, and more. Also, because Alec was co-piloting along live to my livestream, we expected there’d be a stream delay in his responses that we’d have to time shift backward. That wouldn’t have been possible with a single audio stream.

It took a significant effort to capture all audio tracks separately, and it was worth it. Techniques used:

- In Streamlabs OBS - you can output separate audio tracks but you MUST output in .mkv video format and it doesn’t work correctly when streaming (so, local recording output only). Separate your microphone and desktop audio into two different tracks.

- For Zoom calls - Zoom calls come through “desktop audio” which means they aren’t separated from the sim audio. Due to this, if I flew with a co-pilot, I had a second machine running Zoom and a second copy of OBS. I streamed my sim to YouTube, the co-pilot called in on Zoom while watching the YouTube stream and talking to me on a second headset. Second computer, second headset, second OBS recording locally.

- For Compilation and Production - Adobe Premiere does not read .mkv files. You must break them apart into separate .avc and .aac files. I recommend mkvtoolnix for this.

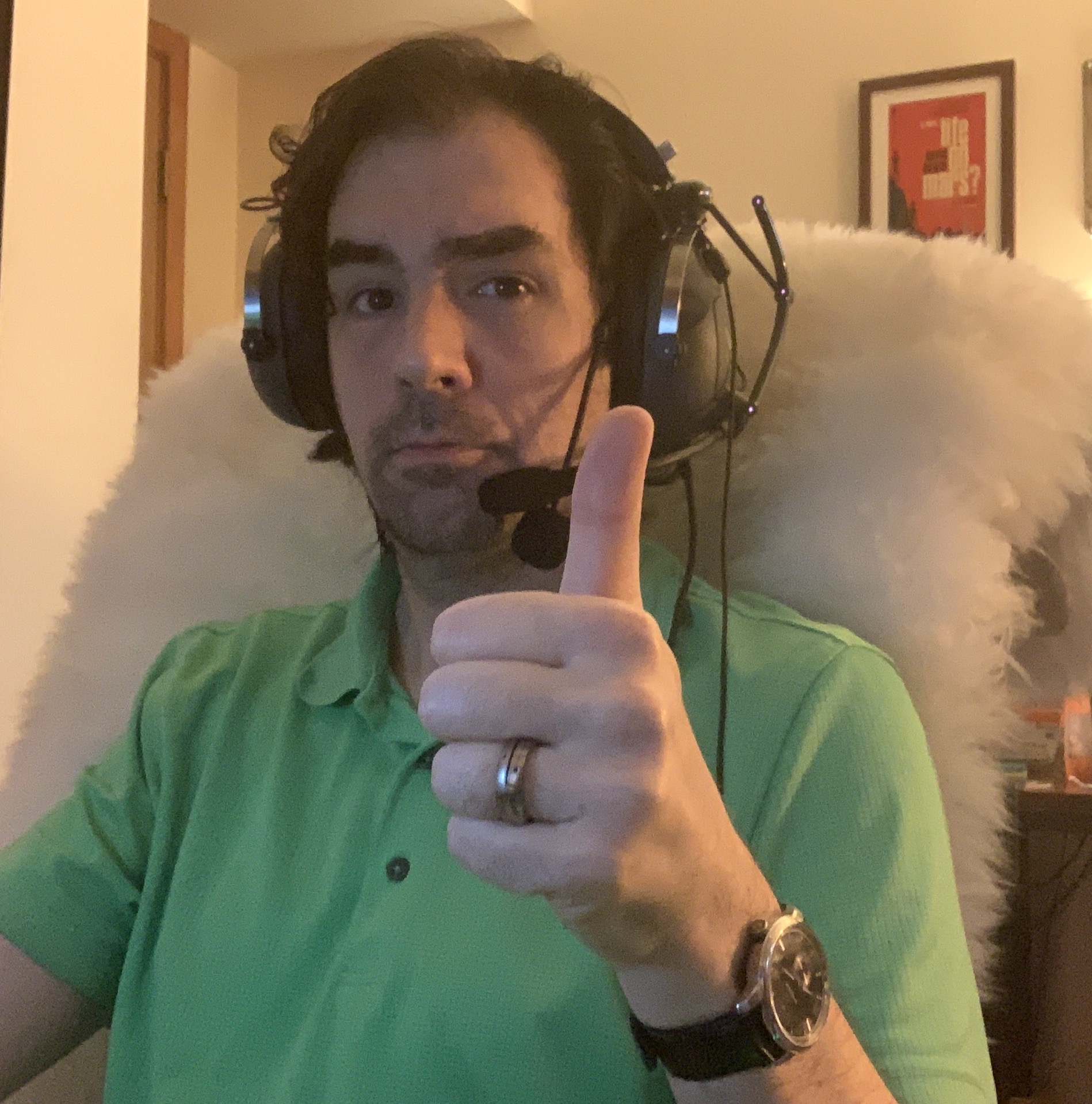

Pictured: The Project Nimitz USAF Thrustmaster Headset and the Project Tusk Razer Ifrit, layered one over the other.

Pictured: The Project Nimitz USAF Thrustmaster Headset and the Project Tusk Razer Ifrit, layered one over the other.

YouTube unlisted livestreaming as review mechanism

Both Alec and our guests needed to be able to watch footage (in Alec’s case, live, and in our guest’s case, pre-recorded) and comment.

For this, YouTube livestreaming in Ultra-Low-Latency mode, with an Unlisted link, worked fine. Overall we saw delays of between 3 and 7 seconds with both parties on the West Coast US. As mentioned above, since we captured all audio tracks separately, it was not overly difficult to simply time shift out the delay and make it sound very close to live.

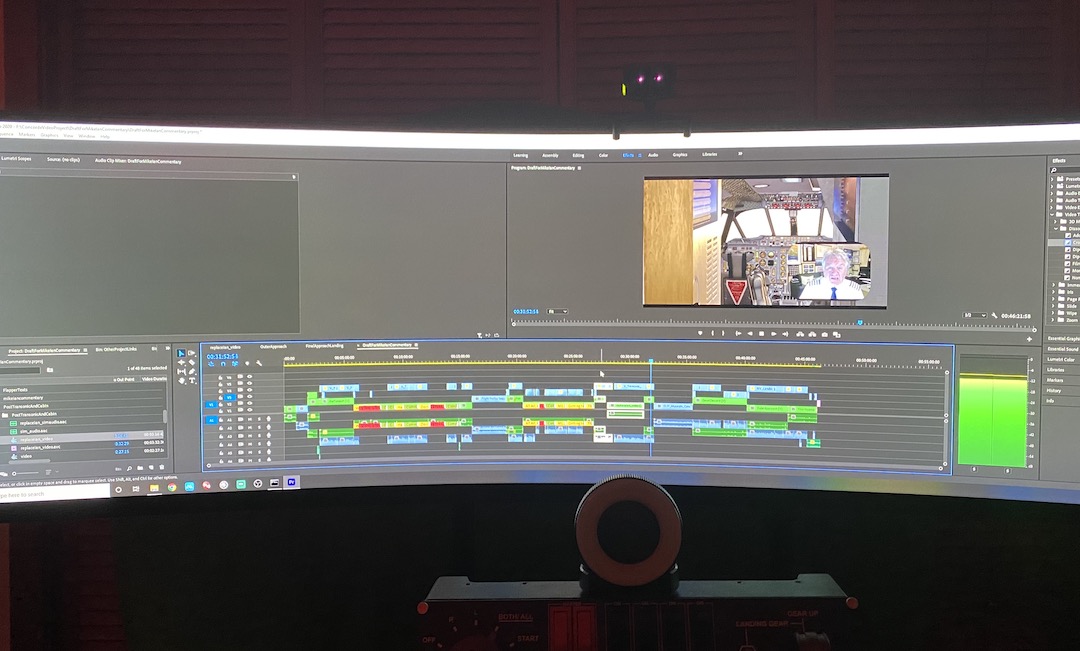

Production intake - tag everything, match marks, one mega-folder

Pictured: The final show timeline in Premiere.

Pictured: The final show timeline in Premiere.

A grab-bag of tips here:

- Once we had all audio and video from the sim for procedures, it was a small set of massive audio and video files. The key was to tag these into audio-video clips. I created sequences of each in order to line up audio and video, then used Adobe Prelude to quickly meta-tag interesting commentary since that was the stuff most likely to move (the procedures themselves mostly went in as-is). The tagging names focused on the speaker, and a notable quote.

- Time shifting Alec’s audio back to mine took some work, as the speed-of-light delay as he watched my YouTube live stream was variable between 3 and 7 seconds, it never stayed consistent. So, as needed, I’d create gaps in the audio track in Sequence view by using the razor tool, then slide around his audio to match known “marks” that were interesting interplays between us. I’d mark my part first with Mark Clip, then mark his part with Mark Clip, then match the marks together.

- I had to move production from one computer to another at some point. It ended up being 100 GB of files, easily. To ensure the project was fully portable with no broken links, the entire thing went under one mega folder with subfolders, which allowed it to be zipped up and transported. Also allowed for easy backups.

Production audio - leave levels until last

We worked drafts until the final day before showtime. Draft five was the final draft. At that point, things had stopped moving on the timeline. I’d purposely left mastering until the end. We ended up cutting a lot of mine and Alec’s audio to give more time and attention to our guests, and it was the right choice. Our guests came through clearly, their stories and experience were front and center, and by talking less, Alec and I came off looking even more professional. We were just here to fly your plane, gentlemen.

Streamyard for final streaming had quality issues

In order to live-stream the produced output and allow our guests to take Live Q&A after the show seamlessly, the Museum used a tool called Streamyard. Overall the tool did what it was supposed to, but in playing back the show footage we had provided, both audio and video from the simulator suffered significant compression effects, leaving the sim experience sub-par. Overall it was still a good show, but modern sims have so much detail it’s a shame to miss any of it. We’ll be experimenting with this and competing technologies to try to find a good balance between flexibility and fidelity.

For Future Sessions

We’re taking our own internal retrospective notes to try to make future episodes even better. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on the final production. If you’d like to give me your thoughts, don’t hesitate to reach out to charles.cox@gmail.com and let me know.

It was a pleasure to be able to develop this show with our distinguished guests, and despite the challenges - or perhaps because of them - the production pipeline we built came out surprisingly robust. I’m proud of it, and proud of all our Future Leaders for continuing to innovate during this unprecedented time, in order to bring the magic of flight to our audiences. Thank you for all you do.